I was diagnosed with chordoma almost 40 years ago: late in the fall of 1983. I had been playing in a golf tournament, and the next thing I knew I was seeing two golf clubs and two golf balls. I looked at my caddie and said to him, “I have a brain tumor.” I finished up the tournament, losing on the 18th hole.

I spoke to numerous physicians and a neurosurgeon to try to find out what was going on in my head. A few doctors said, “You have one of three things: diabetes, diabetes, or diabetes.” Eventually, I was placed in a CT scanner, which took an hour or two to scan my brain. While I was on the table, the CT tech came in and told me they’d have to repeat it, so I knew I had something going on that wasn’t so good. (In 1983, you can just imagine the type of equipment they were using; MRIs had only just been invented and were not in wide use yet.)

Even when I did get my chordoma diagnosis, the doctors essentially said, “We don’t know what this is. We don’t know how to get to it. And we won’t know what to do when we get in there.” They pulled out their books from medical school. Chordoma was never taught to them.

Around that time, my father spoke with a neurosurgeon whom he knew, who explained to him that he had just been at a meeting where they’d discussed the fact that at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, they had a cyclotron — a proton therapy machine — and were doing experiments on people who had chordoma as well as eye cancer. So, for my next adventure, I was put on an airplane to Boston with my father, where we met with the Chief of Neurosurgery, who was heading up the research project in collaboration with Harvard, where the cyclotron building was located.

The team there explained that I had one year to live, but that they had put together a plan to try to help patients like me. So we flew home, talked to my doctors, and set up a plan of attack. The researchers had me sign a release form, and I checked into MGH, where I first underwent neurosurgery (a trans-sphenoidal biopsy). No one had prepared me for the amount of pain that I was going to encounter in the six-day hospital stay following my surgery, with pain medication shots every four hours. I was released from the hospital six days later, after having a plastic mask made of a mold of my head and my face that had an old wooden tennis racket frame which was used to keep the rackets from warping, which was placed at the base of the mask to keep me from moving my head.

We found a place to live nearby and my daily treatments began. I would drive five days a week from Brookline to Harvard, and then to the Harvard cyclotron building. The building and the cyclotron were built in the 1940’s. It was an old science building, and the treatment room and table looked like something out of a Frankenstein movie. The mask that they made for me out of plastic had a mouth piece that they cut in two so I could talk with them during treatment. The mask was bolted to the metal table using wooden C-clamps that you would’ve used in shop class in junior high school.

Every day they would place me on the table, and take X-rays from three different angles of my head, using an Apple-1 computer that MIT scientists programmed to help align the X-ray equipment with my head.

They then would leave the room, lock the door with a bicycle lock, and let me know through a speaker that I should stay still until they returned to tell me they were done. This process could take an hour or two, depending upon how cold it was outside and how long it would take the cyclotron to warm up.

I did this from October 21 until December 30, 1983. After I finished my last treatment, a friend of mine came into town to help me move back home on that same day.

In my long chordoma survivorship journey since then, I have been living with continued double vision, and have had two surgerys to make it go away. The surgeries helped for a while, but the double vision came back pretty fast. I have headaches, a buzzing in my ears, fall up and down stairs, and have been diagnosed with hypopituitarism.

Five years ago, I had a seizure and was rushed to the hospital; I was diagnosed with a meningioma in my right frontal lobe. I had that removed, but then got E. Coli in my brain, which almost killed me — I ended up in the neurointensive care unit for a month.

But I am still here.

Back in 1983, there were no organized chordoma support groups. And since the doctors told me that I only had a year to live, they didn’t speak to me about the long-term battles that I would have ahead of me, or the issues that I’d be going through after my surgery and experimental therapy. They just didn’t think I’d live long enough to have to deal with any long-term side effects.

But throughout my time as a patient and survivor, the love from my wife, my brother-in-law and sister-in-law, my daughters, and the rest of my family and friends made my struggles easier. And in more recent years, the Chordoma Foundation has played a role, especially by connecting me to other patients and survivors and encouraging me to reach out to help others. The Foundation is doing wonderful work in educating people about chordomas. I am confident that one day they will find a cure for this.

I’m proud to say that in 2015, I helped establish the Beaumont Hospital Proton Therapy Center in Michigan, petitioning the governor in person to help fund a proton cyclotron there. I told them how the treatment had saved my life, and enabled me to become a father and then a grandfather.

If I were to offer advice to a newly diagnosed patient now, I’d remind them that this is a battle, and not just one battle. But I’m here to tell you: You do not have an expiration date! Live life, be happy, and smile. Stay positive like the protons!

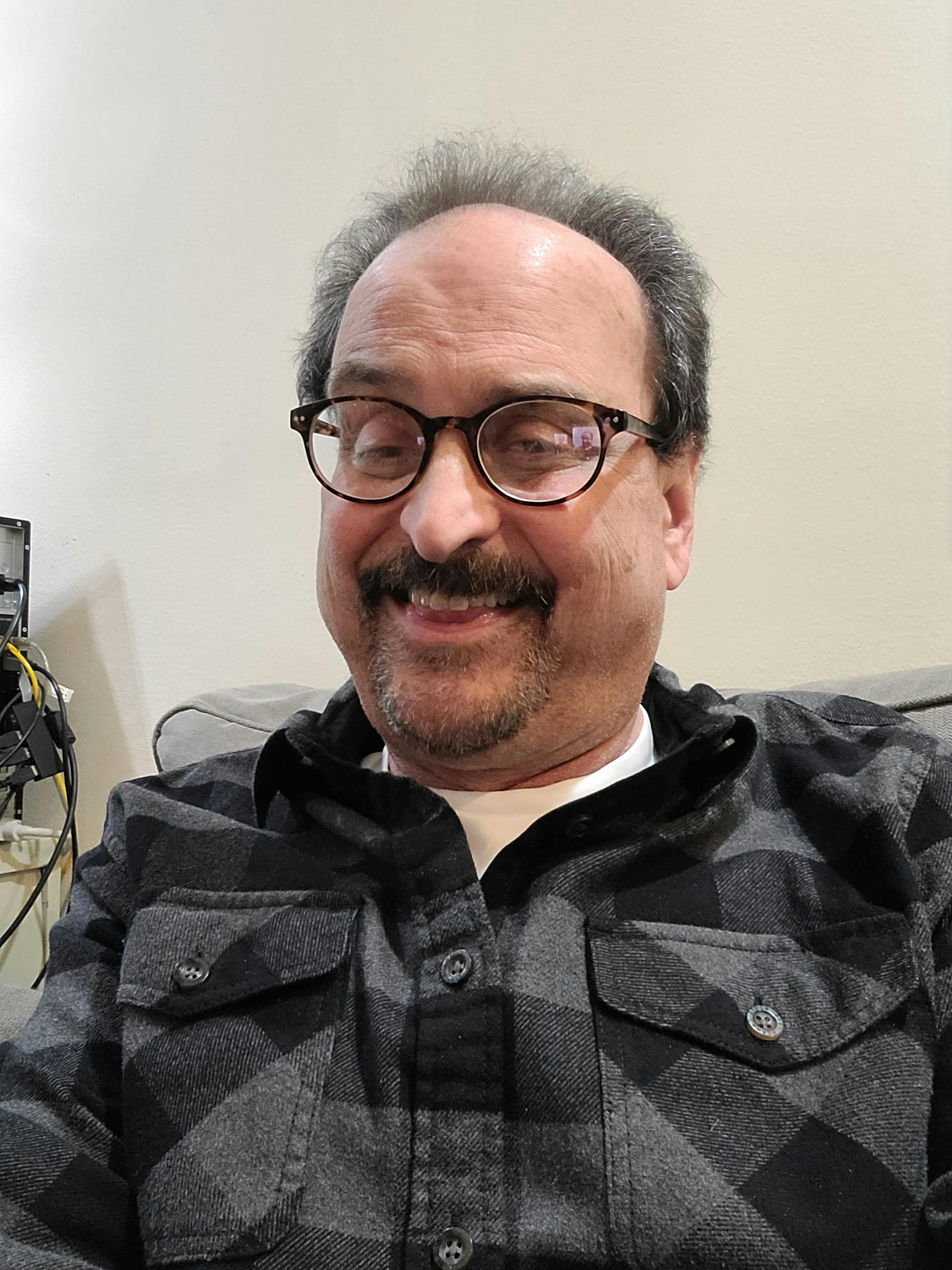

Jonathan’s family today