Get support

Our Patient Navigators can provide more information on side effects like mobility.

A diagnosis of a rare cancer like chordoma doesn't just affect your body. Learning you have chordoma, managing treatment, and dealing with physical side effects can also affect your mind, bringing up many feelings and emotions. Some might be familiar feelings, while others might be new or confusing. Whether you’re currently in treatment, finished with treatment, or supporting a loved one with chordoma, it is normal to experience feelings such as anxiety, fear, depression, and grief.

Just as you would seek support to address any physical challenges related to chordoma, it is also important to care for your mental and emotional health. There are ways to manage your feelings and support emotional wellness throughout your journey, and you don’t have to do it alone.

This booklet will help you:

Understand mental and emotional health and the impact they have on your overall health

Recognize and acknowledge your emotions

Talk with your doctor about what you’re experiencing

Learn strategies for managing distress and other emotions

Get help and support to improve your emotional wellness

Mental health includes emotional, psychological, and social well-being. A person’s mental health affects how they feel, think, and act and helps determine how well they handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.

Emotional health is one aspect of mental health. When a person is emotionally well, they are aware of their emotions and can manage and express both positive and negative emotions accordingly.

Being aware of how you’re feeling starts with knowing how to recognize and identify your emotions. Doing so can help you see the impact your emotions have on your overall health and find ways to regulate and manage them.

The Chordoma Foundation is a resource for anyone affected by chordoma, at any stage of your journey. We're here to help you understand the disease, its side effects, find qualified doctors, and connect with others in the chordoma community.

The emotions we experience are often the result of some kind of stress, either positive or negative, in our lives. Stress is a normal response to life events, but it can also cause mental and emotional health challenges. Stress can be “good stress”, which is often short-term and is related to more positive life events like moving to a new home or starting a new job. Stress can also be longer-term and more severe, such as dealing with food or housing insecurity, the passing of a loved one, or managing a health issue like cancer.

Distress occurs when any type of stress exceeds a person’s ability to manage it, causing sorrow, pain, anxiety, fear, and more. It is common for people with cancer and their caregivers to experience distress at some point during their journey with cancer. When this happens, some of the most common emotions that follow include:

Anxiety: Feelings of fear, dread, and uneasiness. Anxiety is sometimes described as a type of fear that has to do with something going wrong in the future rather than right now. It can cause sweating, restlessness, tension, and rapid heartbeat.

Anger: An emotional state that can range from feelings of mild irritation to intense fury and rage. It can have physical effects such as increasing your heart rate, blood pressure, and adrenaline. Anger can be a good thing if it prompts you to express negative feelings in a healthy way or motivates you to find solutions to problems. However, it can also make it difficult to think clearly or make you want to cause harm to something or someone.

Depression: Ongoing feelings of sadness, despair, loss of energy, and difficulty dealing with everyday life. Other symptoms of depression include feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, loss of pleasure in activities, changes in eating or sleeping habits, and thoughts of death. Different from ordinary sadness, which comes and goes, clinical depression doesn’t go away easily and can affect all aspects of life.

Fear: One of the most powerful and automatic emotions. Fear is caused by the anticipation or awareness of danger. After treatment ends, one of the most common concerns survivors have is that their chordoma will come back. The fear of recurrence is very real and entirely normal. Signs of fear may include increased heart rate, faster breathing or shortness of breath, sweating, chills, and upset stomach.

Grief: Deep sadness and sorrow in response to a significant

loss. Grief is often related to the death of a loved one, but

it can also be the result of experiences such as the loss of

identity or physical function from a serious, long-term illness.

It may include feelings of great sadness, anger, guilt, and

despair. Physical symptoms, such as not being able to sleep

and changes in appetite, may also be part of grief.

There is evidence that people who have been diagnosed with cancer are more likely than the general population to experience mental and emotional health challenges. Being diagnosed with and managing a life-changing disease can cause unwanted or overwhelming distress that interferes with quality of life. While some stress is normal, remaining in a heightened state of distress for long periods of time can negatively impact your physical health and well-being. Fear of disease recurrence, alteration of identity, and perceived (or actual) loss of connection with friends and family can make this already challenging situation feel even harder.

The Chordoma Survivorship Survey, completed in 2021, found that it is common for chordoma patients and survivors to experience a range of emotions such as anxiety, fear, depression, and sadness, both during and after treatment. The survey also found that several of these emotions are even more common among co-survivors, which includes spouses, partners, parents, family members, and friends. Yet, the survey also found that, despite how often they’re experienced, few people access adequate care for these challenges.

Caring for someone with cancer — whether you’re the main caregiver or a supportive family member or friend — often brings with it emotional distress that can feel overwhelming. It’s important for co-survivors to be aware of how their emotional and mental health are being impacted and get support when needed.

Research has shown that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is more common in cancer survivors than in the general population.

Following any distressing or traumatic event, it is common and normal to experience fear, feel anxious, have bad dreams, or avoid situations that remind you of the traumatic event.

Most of the time, these symptoms go away after a few days or weeks. If they do not, they can begin to severely impact everyday life and lead to PTSD, which is a clinical diagnosis recognized by doctors and mental health professionals around the world.

PTSD is historically associated with experiences like war, natural disasters, violence, abuse, or serious accidents, but more recently, mental health professionals have recognized that other life events, such as dealing with cancer, can cause PTSD, too. Receiving a cancer diagnosis, undergoing treatment, dealing with side effects, and facing repeated tests and imaging are aspects of a cancer journey that can cause trauma-related symptoms and lead to PTSD.

Sometimes, people who experience trauma undergo a kind of transformation afterward, developing a new understanding of themselves and the world they live in. Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is the concept that people often see positive growth after dealing with adversity and stress. For instance, cancer survivors and their families sometimes say that following diagnosis and treatment, they appreciate little things in life more and have a more positive outlook.

If you think you are experiencing symptoms of PTSD, talk with your doctor or mental health care provider.

Both during and after chordoma treatment, it is normal to

experience stress related to all the life changes you are going

through. When you first learn that you have chordoma, you may

feel like your life is out of control. Doctor visits and treatments

disrupt your normal routine. People use medical terms that you don’t

understand. You might not be able to do the things you enjoy. And

the effects that chordoma and its treatments have on your body can

make these feelings worse.

Factors that increase the risk of normal, expected stress causing emotional distress are often related to chordoma, but other aspects of life can contribute as well. These factors include:

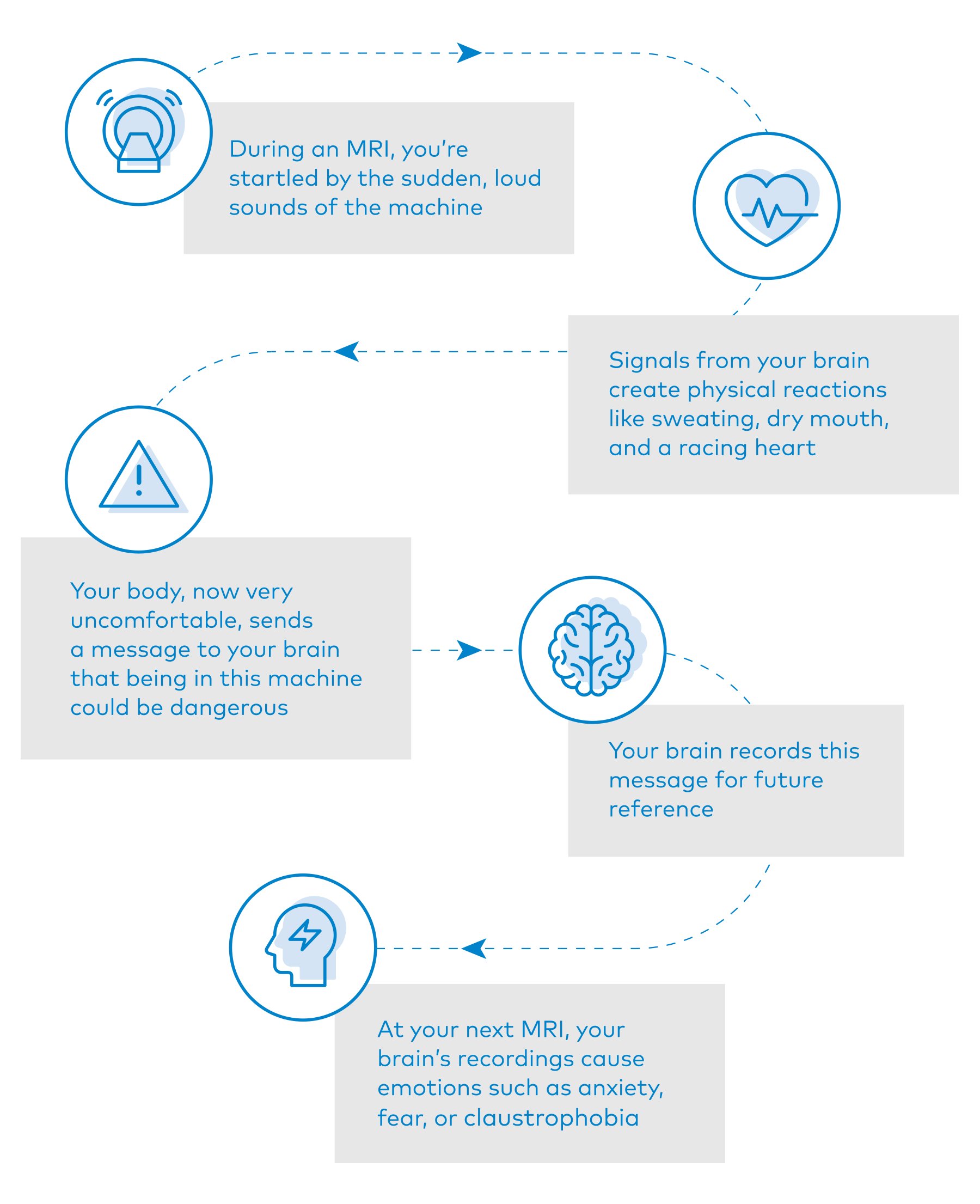

Doctors and researchers have studied the connection between our brains and our emotions since the earliest days of science. We now understand that an experience can prompt the brain to send signals through the body that automatically and unconsciously create physical reactions. These physical sensations instantly send messages back to the brain that it interprets and records. Those interpretations and recordings are what prompt our experience of having emotions. Here’s a possible scenario:

The field of neuroscience has made great progress studying the connection between our brains and our emotions, and there is still a lot to be learned. Research has found that our individual brain chemistry plays a key role in how we each process and communicate emotions. What causes one person great emotional distress may be manageable for someone else. What we do know is that our emotions are not faults or weaknesses, but rather a result of the communication between our bodies and our brains.

The successful completion of active treatment is an important and exciting milestone for anyone who has dealt with chordoma. The resulting transition to survivorship usually means fewer medical visits and less direct support from the medical team that rallied around you during treatment. There are often expectations (yours or others) that you should be celebrating or relieved that treatment is complete and ready to return to “normal life”.

However, the shift to managing the physical and emotional ups and downs of life as a “survivor” is experienced differently by each person. For some, this transition can sometimes cause feelings of distress to intensify. If you notice this happening to you, talk to your care team and ask about support and treatment options.

Although the mind and body are often viewed as being separate, mental and physical health are closely related. Good mental health can positively affect your physical health. In return, poor mental health can negatively affect your physical health.

Research has found links between chronic mental and emotional stress and immune function, with greater distress contributing to less effective immune responses.4,5 Too many stress hormones increase inflammation in the body, which hinders the immune system. A weakened immune system can make it easier for cancer cells to grow and harder for them to die.

Emotional distress can have serious impacts on your everyday life, as well. You may find it more difficult to concentrate on work or school, to interact with people socially, participate in activities you normally enjoy, or take care of yourself and your family.

If feelings of distress, anxiety, depression, or fear consistently last for more than a few weeks or begin to affect most aspects of life, making it hard to function or cope, it is important to seek help.

The emotional, social, spiritual, and physical impacts of chordoma affect you in different ways at different times, so it’s important to take the time to ask yourself questions such as:

What feelings am I aware of having right now?

Which of these feelings is the strongest?

When did I start feeling this way?

How are these feelings impacting my thoughts and actions

Most of us rarely stop to check in with ourselves in this way. We tend to think of things more generally: I’m in a good/bad mood today, or I’ve got so much to do and don’t feel like being social right now. But we don’t recognize the emotions behind these thoughts. It’s also common to feel pressure to put on a good face or appear strong for others while dealing with chordoma. But doing so can lead to feeling even more lonely or isolated.

Pause for a few moments throughout every day to ask yourself questions like those listed above. This can help you name and track your emotions, making it easier to see patterns that indicate the difference between ordinary emotional ups and downs and more serious emotional distress.

As soon as you notice your emotions beginning to interfere with your

ability to function, even if you think your feelings or thoughts are

minor, talk to your care team about what you’re experiencing.

Remember that your care team is treating YOU, not just your chordoma, and they count on you to tell them how you’re feeling. While it may be difficult to talk about your emotions, you’re not alone. It’s okay — and important — to ask for help.

Signs that you should seek help include:

• Your feelings don’t lessen or go away

• Your feelings keep you from doing normal activities and interfere with your ability to function

• You are constantly overwhelmed or to the point of panic • You don’t enjoy doing things the way you used to

• You are having suicidal thoughts

Nurses, oncology social workers, and patient navigators may conduct periodic distress screenings at appointments during and after your treatment. They may use a questionnaire or a 0 to 10 scale, similar to the way they ask patients to report pain. A standard scale used by many cancer care teams is the Distress Thermometer, which is usually accompanied by a checklist of possible issues, to reflect how much and what kind of distress you feel today and how much you felt over the past week.

Your doctor or care team will then work with you to determine the right support to meet your needs. But you don’t have to wait for a distress screening to ask for help. You should contact your care team at any time to discuss any distress you may be feeling.

Suicidal thoughts are thoughts that life isn’t worth living or when you’re thinking about or planning to harm or kill yourself. This is a very serious symptom of clinical depression that you should never keep secret. Tell a family member, friend, or your doctor immediately if you’re experiencing these thoughts.

If you feel you’re in crisis and cannot reach your doctor or a loved one, call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at +1 (800) 273-8255 or visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention at findahelpline.com for helplines in other countries.

Emotional distress associated with chordoma is common and manageable. Keeping your care team informed about your emotional experience will help them connect you to the right support services so you can concentrate on getting, and staying, well. These may include medication, mental health services such as counseling and support groups, relaxation therapies, creative therapies, or some combination thereof.

The American Cancer Society offers some suggestions on do’s and don’ts for managing distress, including:

DO:

DON’T:

On the other end of the emotional spectrum, confronting chordoma has been known to inspire feelings of hope and gratitude. Some people view their chordoma as a “wake-up call” and take from it the ability to notice and appreciate the little things in life, like spending time with friends and family, enjoying nature, or mending broken relationships.

But for others, hope and gratitude must be cultivated and practiced

intentionally. This doesn’t mean you have to ignore difficulties or

force yourself to be positive and upbeat all the time. Instead, try

to think about what you’re experiencing from different viewpoints,

focus on caring for yourself, or celebrate little victories along the

way. Practicing gratitude can play a key role in developing healthy

ways to cope in times of stress.

Everyone affected by chordoma deserves to feel connected to someone who understands the experience and can help process the emotions that come with it. Asking for and accepting help from others is an important part of coping with emotional distress. There are lots of ways to find and get help.

Ask your doctor for a referral to a licensed counselor or mental health specialist, or seek one out yourself. These professionals include:

Use online directory tools to find a mental health specialist anywhere in the world, such as:

PsychologyToday.com/intl/counsellors, OnlineTherapy.com, and InternationalTherapistDirectory.com

Explore mental health and meditation apps from the comfort of your home using a smartphone or tablet.

Contact the resource center at your local cancer treatment center to ask about classes, social support, and counseling options near you. Cancer support organizations, whether local or national, can also provide support and guidance.

Learn how to cope with your diagnosis

Manage anxiety, depression, fear, and grief

Feel less overwhelmed and more in control

Cope with symptoms and side effects, such as pain and fatigue

Deal with emotional concerns about self-image, body image, or intimacy

Manage fears or worries about the future

The following resources can help you manage distress and support your overall emotional health.

Mental health professionals evaluate and treat all types of emotional distress and mental health challenges, whether moderate or severe, using a range of counseling approaches. Support groups can also help by connecting you with others who have shared experiences.

Activities that help you relax often help ease some forms of distress. These might include relaxation exercises, mindfulness, meditation, massage, and guided imagery. Creative therapies like art, dance, and music have also been shown to be helpful for people in stressful situations.

In a time of crisis, many people prefer to talk with a person from their spiritual or religious group. Today, many clergy are trained in counseling people with cancer. They’re often available to cancer care teams and will see patients who don’t have their own clergy or religious counselor. Churches often offer faith-based support groups as well.

Sometimes medicine is needed to reduce distress related to chordoma, or counter the emotional health symptoms caused by treatment. Medications for depression and anxiety are prescribed by psychiatrists and some general practitioners, and are usually taken while a person is receiving some type of counseling to support them as well.

Exercise is not only safe for most people during and after chordoma treatment, but it can also help you feel better. Moderate exercise has been shown to help with tiredness, anxiety, muscle strength, and heart and blood vessel fitness. Even light exercise, such as yoga, walking, or stretching can be helpful in staying as healthy as possible. Talk with your doctor before you start so you can make an exercise plan that’s safe for you.

Having chordoma can affect your day-to-day needs. There are common, practical problems that a Chordoma Foundation Patient Navigator or an oncology social worker can help you and your loved ones address. Some practical challenges they can help you navigate include transportation needs, financial concerns, job or school concerns, help with daily activities, and cultural or language differences.

One of the most important — but often overlooked — tasks for caregivers is caring for themselves. A caregiver’s physical, emotional, and mental health is vital to the wellbeing of the person who has chordoma.

As a caregiver, you may experience periods of stress, anxiety, grief, depression, frustration, and more. These are all common emotions for caregivers to have, and you don’t have to deal with them alone. Talking with other people who are caring for a family member

or friend with chordoma can help you cope. So can talking with

a licensed counselor individually or as part of a support group. Oncology social workers, cancer resource centers, and your own general practitioner can help you find local support networks and resources in your area.

Some strategies for coping include:

Recognizing the signs of stress. It may be time to seek help if you are feeling exhausted all the time, getting sick more than usual, having trouble sleeping, feeling impatient, irritated, or forgetful, not enjoying things you used to enjoy, or withdrawing from people.

Accepting help from loved ones. Family, friends, and members of religious and community groups are often willing to assist with caregiving, chores, errands, or childcare. Accept their help and give them specific tasks. Consider making a list of family, friends, neighbors, and local organizations who can help and what tasks they are available to do.

Making time for yourself and other relationships. Spending time doing something you enjoy, with someone whose company you enjoy, can give you a much-needed mental and emotional break. Those supportive relationships are important for your own health and well-being.

Learning about family and medical leave. There may

be programs available to you through your employer or government that provide time off to care for a seriously ill family member.

Being kind and patient with yourself. Many caregivers experience occasional bouts of anger or frustration. And then they feel guilty for having these feelings. Try to find positive ways to cope with these difficult feelings. This could include talking with supportive friends, exercising, or journaling.

Taking care of your body. Make time to exercise, eat healthy foods, stay hydrated, and get enough sleep. Also, re-evaluate your own health. The stress of caregiving can lead some people to develop or increase unhealthy habits, such as smoking, drinking too much alcohol, or using prescription medicine improperly. If you cannot make healthy changes on your own, seek professional help.

Watching for signs of depression or anxiety, and seek professional help if they persist. Several studies have shown that caregivers are at an increased risk for depression and anxiety. Our own Chordoma Survivorship Survey found that caregivers report emotional health challenges at a higher rate than patients. If you are having trouble coping with your emotions and it lasts more than a few weeks, talk with your doctor or a licensed counselor.

Hear from experts on emotional health in this video about caring from yourself during stressful times.

References and further information

Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415. doi:10.1136/bmj.k1415

Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA, Katikireddi SV, Smith DJ. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):943. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4

Swartzman S, Booth JN, Munro A, Sani F. Posttraumatic stress disorder after cancer diagnosis in adults: A meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(4):327-339. doi:10.1002/da.22542

Dai S, Mo Y, Wang Y, et al. Chronic Stress Promotes Cancer Development. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1492. doi:10.3389/ fonc.2020.01492.

Moreno-Smith M, Lutgendorf SK, and Sood AK. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncol. 2010;6(12):1863- 1881. doi:10.2217/fon.10.142.

Managing Distress. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/treatme... effects/physical-side-effects/emotional-mood-changes/ distress/managing-distress.html.

Last updated February 3, 2020.

Important note about this publication:

This content was developed by the Chordoma Foundation. It is not meant to take the place of medical or professional advice. You should always talk with your health and mental health care providers about treatment options and decisions.

We would like to thank Jennifer Bires, LCSW, OSW-C, and Megan Whetstone, LCSW, for their time and expertise in reviewing this information.

The information provided herein is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your or your child’s physician about any questions you have regarding your or your loved one’s medical care. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.